Part I: Problema (Grande)

Anyone who knows me in my personal life knows that I am terrible at foreign languages. Despite having taken three and a half years of Spanish, I still cannot reliably attribute the correct gender to a noun, let alone verb conjugation. Some of my more infamous flubs include the phrase “I sported it blood up to the Rome,” a debate (held in Spanish) in which I held the floor for so long—and with so little coherence—that I won entirely by confusing my opponents into silence, and a ten-minute conversation in which I tried to say what I would do were I to win the lottery, but accidentally told my entire class that I had contracted an incurable disease. For me, language acquisition is a boring, painstakingly slow process that involves years of work for relatively little reward. But what if it didn’t have to be? What if you could cram a year’s worth of learning into a week? Someone should try that.

Part II: Speedrun

I allowed myself three weeks to learn Mandarin Chinese. At the outset, this seemed like more than enough time, April 15th seemed so far off, there was no need to worry, no need to rush. After all, this wasn’t a speed-race, this was a speed-marathon, and this speed-marathon ended with three trials. The first trial would encapsulate my real world language skills. I would order food from a Chinese restaurant and shock the employees with my perfect Chinese. In the second, I would test my artistic abilities by translating a Chinese poem into English. For the final trial, I would participate in a Mandarin-only debate with another student. The plan was flawless, now I just needed to assemble my team.

In order to best facilitate and legitimize my speedrun, I recruited the help of three trusted coworkers. The first was my co-writer, Fruzsina Roka. She filmed, took photos, set up times for many of the trials, and chose the poem I would translate. She even came up with the language speedrun idea. I could not have done this without her. The second, I could have easily done this without: Jacob Harding. By all means a polyglot, Jacob would be speedrunning alongside me, challenging me to do better and try harder. The third was Aidan Halat, who already spoke some Mandarin and would be moderating the debate. All I had left to do was prepare.

It did not go well.

My preparations were shoddy, to say the least. Over the course of three weeks, I did four Duolingo lessons, listened to a few videos in Chinese and did a bit of writing on a whiteboard. My only saving grace was a study app recommended to me by Fruzsina. With a six-character name I cannot pronounce and a bright red icon, this app was a study tool to help Chinese speakers learn to improve their English. Its short-form video content (akin to Tik Tok or Youtube Shorts) enraptured me, and kept me online in the Chinese speaking world. The only problem was that while it may be successful in teaching English, it was not a helpful study tool for Chinese. I learned no phrases or words through this app, despite my best efforts.

One day, I tried writing a phrase from a video onto the whiteboard in the commons. While admiring my handiwork, a stunned Oliver Xuan came to inform me that I had (incorrectly) written the phrase “How do foreign women say period?” This was news to me, but before I could clear the board, a crowd had formed. I had to wallow in my shame and came into the trials seeking a win.

Part III: The Trials

Trial 1: Panda Express

Fruzsina Roka:

The ordeal began with Calvin pulling up in his 2017 Infiniti Q50. Looking back, I can only mourn the fact that I did not realize that this car was an ominous omen that the upcoming trials would be infinite in strife. However, hindsight is 20/20, and I am terribly nearsighted. We drove for 5 minutes to the zenith of our journey: Panda Express. To pass the time, I recorded Calvin’s thoughts on the upcoming challenge. He practiced what he was going to say, which didn’t reassure me at all. Upon our arrival, Calvin decided to take the drive through, which I enthusiastically agreed to—without a face, I could not be banned from the establishment or put on a fast-food watchlist. As we pulled up to the dingy microphone next to the lit menu, I could hear the whispers of “crab rangoons, please” and “no soy sauce, thanks.” In that moment, I would’ve given anything to be one of those voices, remembered long enough to jot down an order, then promptly forgiven in the din of the hundreds of other customers.

We were not like those customers. Calvin began in broken Chinese: “你好…米饭…冰茶?” [Hello… Rice… Iced tea?] From what he had practiced, I knew he was offering a paltry greeting, along with a request for rice and iced tea. The poor fast food worker, however, was not privy to this information. She remained silent for what seemed like a century before eventually responding. “…Could you repeat that?” Much like Sisyphus, Calvin kept on pushing: “米饭…冰茶!” [Rice… Iced Tea!] Then, the unthinkable happened: the employee hung up. To make matters worse, we were effectively caged in by the white Honda in front of us and the line of cars behind us. Time came to a standstill as the Honda slowly lugged all three bags of takeout, as well as an entire vending machine worth of drinks, into its depths. As soon as the car turned away, we screeched out of the Panda Express. Rather than learning our lesson, though, Calvin cooked up an even better idea: go next door to Cane’s.

He drove us into the drive through, accidentally cutting off a black Ford F350 that showed us a rather unkind hand gesture. This time, Calvin simplified his order, asking simply for a 3-piece combo with a 冰茶, or iced tea. Like a broken clock, though, the employee once again asked, “I’m sorry, could you repeat that?” However, even a broken clock is right twice a day, because when he drove up to the pickup window, THERE WAS THE ICED TEA!!! Calvin shocked the employee into fluent Chinese! We were both incredulous. On the way home, Calvin shared that this trial was likely the easiest in hindsight, and that the real challenge was only just getting started.

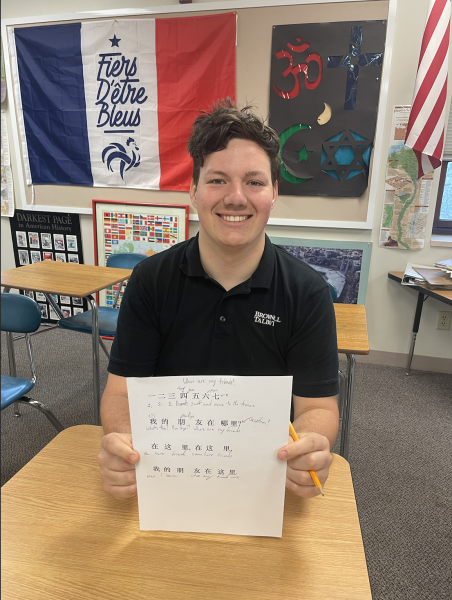

Trial 2: Poem Translation

As Fruzsina noted in her recounting of trial one, the bulk of the challenge lay in front of me. A day passed from my ordeal at the Panda Express, and a dawning (non-xenophobic) terror wormed its way into every inch of my being whenever the Chinese language was brought up. Day Two heralded the second trial: poem translation. For this, Fruzsina selected a poem for me, telling me it was called, “Where is my friend?” What follows is a third party translation of the poem, (which I quickly learned was, in fact, a nursery rhyme) and my own translation.

Original, (English translation courtesy of the Bridgewater youtube channel)

“One two three four five six seven

Where is my friend?

Over here, over here

Where is my friend?”

Translation (Translation courtesy of Calvin Snyder)

“One two three presents surf and move to the treasure

What’s this, buildings? Where are my friends?

Come here friends! Be here friends!

Now I know who my friends are.”

Upon reading my translation, my rival had this to say:

Jacob Harding: ‘The translation is frankly terrible. In the first line, Calvin fails to count past 3, and the rest of the quote unquote ‘translation’ is a vomit of whatever terrible ideas were brewing in Calvin’s mind. It’s a miracle that anyone still talks to him after this.”

Clearly, I had my work cut out for me in the coming debate.

Trial 3: Debate

Fruzsina Roka: By the time Trial Three rolled around, I no longer expected much out of Calvin’s foreign language expertise. In the previous two trials, the only Chinese words I heard him say were iced tea, tofu, rice, and Italy. Sadly, none of my debate questions were on these topics. After Aidan left, I took over as the moderator and began to ask some questions of Calvin and Jacob through Google Translate’s playback feature. These were very basic questions, such as the socio-economic status of the world. As expected, Calvin began to lose, and lose badly, to Jacob. The score was 2.36 to 4.35 after 5 questions, with one final question left: “你喜欢中国吗?” [Do you like China?] Immediately, Jacob began shaking his head up and down in a firm “yes” motion. Calvin did not get the memo. He responded with a decisive thumbs-down gesture and an added “冰”—ice. For that disgusting affront to Chinese culture, Calvin received a 500 point penalty, dropping him down to a -497.64 final score. Jacob, on the other hand, finished with 504.35 points. For his stupendous inability to master the Chinese language, Calvin was also given the death penalty.

Part IV: Speedran

In hindsight, I shouldn’t have thought this would work. Successful language learning requires time, dedication, and persistence if any actual skills are to be acquired, or at least so I’m told. When it comes to language, I am a slow learner with little time for practice. I did next to no studying, which, when combined with a lack of latent talent, ended up with three incredibly embarrassing tasks—a monument to my hubris. In comparison, my much-hated rival did quite well for himself. He practiced daily and already had a penchant for language, and so picked up enough to not embarrass himself. For Jacob, speedrunning worked relatively well. He is/was by no means fluent, but wound up learning some new things in a short period of time. I, on the other hand, only ended up with three relatively useless phrases, two of which were cognates. My ego may be bruised, but at least I have some 冰 to apply to my wound.

Special Thanks to Jacob Harding and Aiden Halat for their contributions to this story.